He Kura Whaikaha, He Kura Whaimana, He Kura Whaiora

Mangakōtukutuku College is a new school in the South-West of Hamilton and will open to students in 2024. This is an exciting opportunity to develop a school with a new vision for 21st Century teaching and learning in the Melville community and surrounding areas. We want to create rich opportunities for our students to grow and develop into forward-thinking and responsible citizens. We are fortunate that our campus is located on the tribal lands of Ngāti Māhanga and Ngāti Wairere, and we are therefore presented with a unique opportunity to draw on tribal knowledge and narratives to support and enrich our potential vision, values, and culture of our new school.

Encapsulated in our school whakatauki are the characteristics of our ancestors, Wairere and Māhanga, who “were both leaders, renowned for their practices of Māori traditions such as weaponry, oratory, navigation and environmental sustainability” (Jones & Biggs, 2004, p. 385). Born in the 16th Century and preluding the Waikato Land Wars of 1863, Wairere and Māhanga were both skilled in the art of tactical warfare, ensuring the safety and protection of their people by only retaliating when necessary. Jones and Biggs (2004) state that, “they were also advocates for peace and would avoid physical confrontation through the art of diplomacy” (p. 401). They were both strong in their tribal identity, smart in their pursuit of self-determination and resilient during difficult and challenging times.

Mangakōtukutuku College is honoured to carry the name and narratives of both Ngāti Māhanga and Ngāti Wairere, and we are equally committed to instilling in our students the characteristics of Māhanga and Wairere. Our hope is that our students will be strong in their own cultural identity and smart in the way they pursue personal excellence.

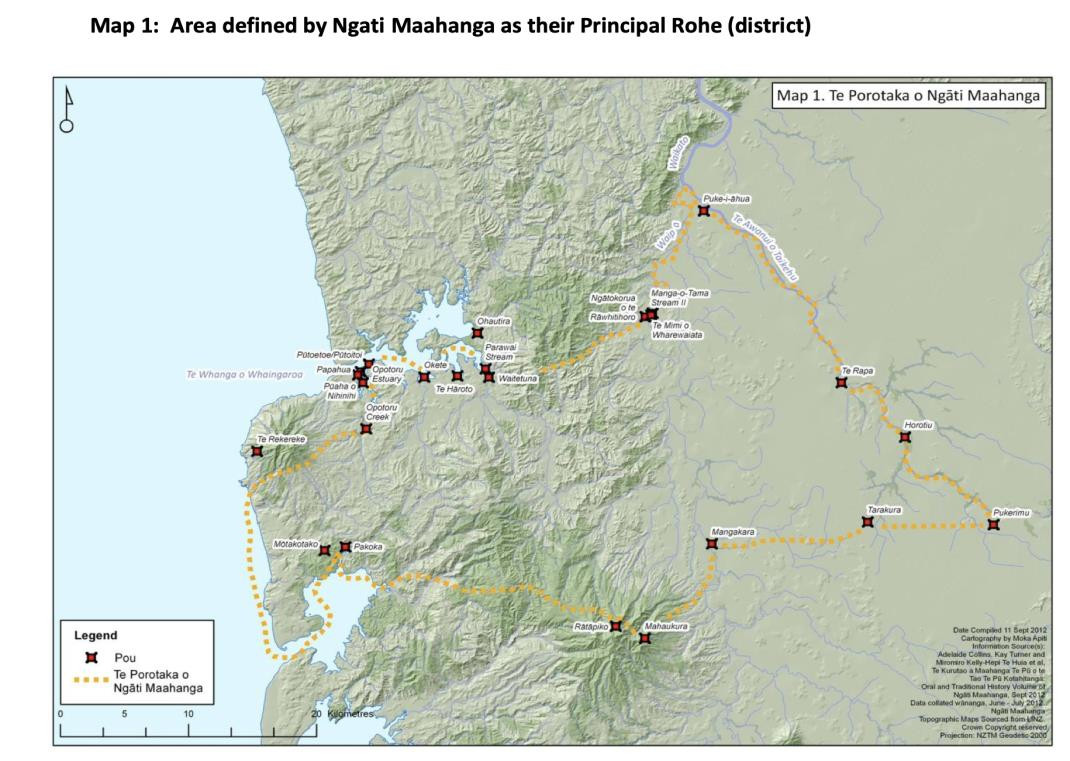

Māhanga is the paramount chief of Ngāti Māhanga and its tribal boundaries begin at “the summit of Pirongia, named Mahaukura. This boundary line runs south to a stream called Mangakara, until it reaches its final resting point of the Waipā river” (MOU between NUoM & Waikato District Council, 2012). These ancestral rivers of Māhanga then flow forth to the rivermouth of Mangaotama. The eastern tribal boundaries of Ngāti Māhanga “begin at Taraakura then continue towards Pukerimu, then onto Horotiu (Narrows Landing). The waters of Te Awanui o Taikehu (Waikato) to Te Rapa (current Waikato Hospital site) symbolises the tribal boundaries within Hamilton City” (Samuels, personal communication, Feb 7, 2023).

Ngāti Māhanga is a principal iwi of Waikato-Tainui and his whakapapa is founded on the tūpuna Māhanga, son of Tūheitia from where the name of our current Māori King was given. Māhanga was a “renowned fighter and was often absent from his ancestral lands due to his involvement in inter-tribal warfare” (Royal, 2017, online) which led to the tribal expression, ‘Māhanga whakarere kai, whakarere waka, whakarere wahine’.

Ngāti Māhanga has five principal marae located within its tribal boundaries. These are

➔ Ōmaero

➔ Te Kaharoa

➔ Te Papa-o-Rotu

➔ Mōtakotako

➔ Te Papatapu

Special acknowledgements must be given to prominent Māhanga leader, Te Awa i Taia, born in the late 18th Century. A skilled fighter in the art of wielding a taiaha, he was instrumental in leading Māhanga forces in intertribal warfare: “Te Awa i Taia was an ally and fighting companion to two of the most famous Waikato warriors, Te Waharoa of Ngāti Hauā, and Pōtatau Te Wherowhero of Ngāti Māhuta” (Samuels, personal communication, Feb 7, 2023).

During the Waikato Land Wars, dissension and division existed amongst Ngāti Māhanga tribal members, “with those who chose to join Tāwhiao’s resistance against government forces labelled as ‘hauhau’” (Samuels, personal communication, Feb 7, 2023). Those that abstained from participating in the war effort, remaining aloof, and to “an extent pro-government were labelled ‘kupapa’ and many tribal members to this day continue to carry the name ‘hauhau’ or ‘kupapa’ in recognition of this accord” (Samuels, personal communication, Feb 7, 2023).

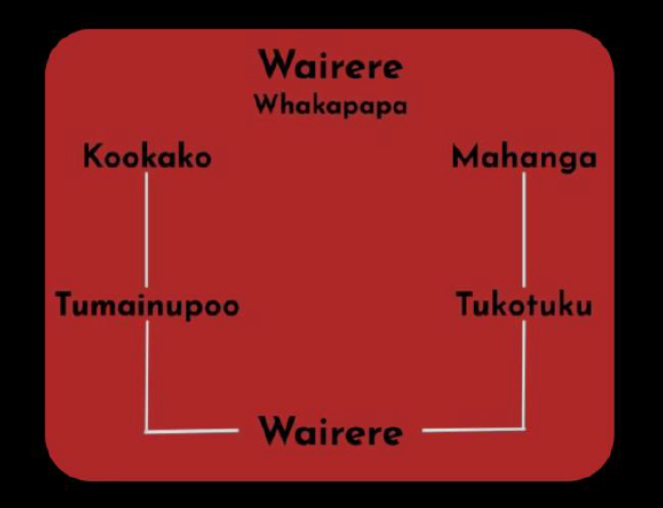

Wairere is the paramount chief of Ngāti Wairere and its tribal boundaries include Hamilton City and its immediate surrounds. Tamainupō and Tukotuku begat Wairere and he was baptised in Te Awanui o Taikehu, near Huntly at Taipouri Island (Ngaa Puna o Ngaati Wairere, n.d., para 1). Te Awanui o Taikehu was the original name of Waikato River, and its change can be attributed to this event.

The name Wairere refers to the many flowing waters within Kirikiriroa that either connect to or run off the Waikato River, and the name Ngāti Wairere refers to “the congregation of descendants who resided on the lands which are now currently known as Hamilton City since the mid to late 16th century” Te Pae Here Kaahui Ako (NPoNW, n.d., para 3).

The 1863 Waikato Land Wars affected many iwi and hapu within Waikato-Tainui, particularly Ngāti Wairere who, according to Jones and Biggs (2004), “resettled at Hukanui Marae in Gordonton. The impact on people, places and the environment was devastating, with multiple casualties resulting in the confiscation of 1.2 million acres of prime Waikato land by Governor Grey and the British army” (p. 174).

The historic 1995 Waikato Raupatu Settlement acknowledged the wrongful confiscation with a Treaty settlement of $170 million, and a world first formal apology from Queen Elizabeth II herself to Te Arikinui Te Atairangikaahu and Waikato-Tainui dignitaries and kaumātua (New Zealand Legislation, 2021).

Ngāti Wairere maintains its mana motuhake over its tribal lands and their place of belonging or ‘tūrangawaewae’. This is best summarised in their tribal narrative which is etched in Ngāti Wairere tiriwhana that states: “Ko Taupiri, ko Hangawera, ko Pukemokemoke ngā maunga. Ko Waikato, ko Mangatea, ko Kōmakarau ngā awa. Ko Hukanui, ko Tauhei ngā marae. Ko Wairere te tangata. Ko Tainui te waka. Ko Ngāti Wairere te iwi” (Hopa, personal communication, February 17, 2023).

There are seven hapū that make up the Ngāti Wairere tribal confederation, with a total of five main buildings on each of the two Ngāti Wairere marae. Historically, Ngāti Wairere had the largest contingent of tribal members onsite prior to the building of Tūrangawaewae Marae. These are traditional whare that each serve a historical purpose. The wharenui on Hukanui marae is named Tūturu-ā-Papa Kamutu and was named by King Tāwhiao, the second Māori king, who lived on the marae for some time. Originally named Tūturu-ā-Papa, the latter part of the name, Kamutu, was added when the practice of Mākutu (witchcraft or black magic) ceased. King Tāwhiao at the time gathered tohunga and abolished this practice. This is just one example of the deep, historical narratives that are etched in the names of all whare that stand upon the tribal lands of Ngāti Wairere. Te Pae Here Kaahui Ako (NPoNW, n.d., para 3). There are also significant relationships between Ngāti Wairere and Ngāti Hauā, particularly during the time of the establishment of the Kīngitanga and the need to unite Māori during difficult and trying times.

Mangakōtukutuku College acknowledges Ngāti Wairere and Ngāti Māhanga as our mana whenua and we are honoured to draw upon their stories and narratives as the foundation for our cultural narrative. As a school we are cognisant of the care and sensitivity that must be exercised by our team when working in partnership with multiple mana whenua. Both Ngāti Māhanga and Ngāti Wairere maintain their own rights and mana as individual tribes with their own jurisdictions, and their shared whakapapa underpinned by kotāhitanga is clearly evident in the relationships between each tribe. To elevate the mana of one particular mana whenua above the other would be disrespectful and would be of disservice to those students who have tribal affiliations to either Ngāti Māhanga, Ngāti Wairere or both.

Wairere was the son of Tamainupō and Tukotuku. Wairere’s father, Tamainupō, descends from the Eastern Bay of Plenty and provides an ancestral link between Waikato and Mataatua. Wairere’s mother, Tukotuku, is the daughter of Māhanga, thus creating an important genealogical link between Ngāti Wairere and Ngāti Māhanga. The two ancestors are inextricably linked through bloodlines and whakapapa.

It is through the notion of kotāhitanga and whanaungatanga that we have developed our cultural narrative and will use this as a basis of how we will work in partnership with mana whenua, in the same way that Ngāti Māhanga and Ngāti Wairere did in the early 16th Century.

Mangakōtukutuku is the name given to the local area based on the native fuchsia tree that was commonly found particularly near waterways. The name itself dates to the early 16th Century during the time of Wairere and Māhanga and is now given to the stream that runs through the gully.

The Mangakōtukutuku Stream catchment originates in agricultural land south of Hamilton before entering the southern suburbs of Glenview, Bader, Melville, Sunnyhills and Fitzroy, and merges with the Waikato River opposite the Hamilton Gardens. There are around 34km of stream mapped in the Mangakōtukutuku catchment. In addition to the three main branches which have rural headwaters, there are several small tributary streams. Borrow pits and other archaeological features indicate that the Mangakōtukutuku area has a rich Māori history and includes several pā sites. Ten species of native fish are known in the Mangakōtukutuku Stream system.

A range of native birds, bats, lizards, and invertebrates have been seen in the Mangakōtukutuku gully system including puriri moth, glow worms, the giant bush dragonfly, and tree weta. Birdlife includes kererū, tūī, bellbird, fantail, harrier hawk, silver eye, grey warbler, kingfisher (Kotare), white-faced heron and ruru (morepork). These species use the kōtukutuku tree for nourishment.

Kōtukutuku particularly likes to grow alongside streams and rivers. It is the world’s tallest fuchsia, growing up to 12 metres tall. Kōtukutuku is one of Aotearoa-New Zealand’s few deciduous native trees, its name references the tukutuku or ‘letting go’ of its leaves each winter. The flowers grow straight out of mature wood, and they are yellow-green when they first open, changing to purple-red as they mature. Male and female flowers often appear on separate trees, but some trees have dioecious flowers (i.e., flowers which are bisexual).

It is also a rich source of nectar for birds such as tūī, tītapu, korimako, hihi and pihipihi. "When the Kotukutuku flower is green that is when it has all the nectar. When the Kotukutuku flower is red and purple in colour, there is no nectar. The birds and insects know when there is no nectar". (Taylor, personal communication, April 2023). While feasting, the birds get covered by distinctive blue coloured pollen. The succulent berries are called konini. From a single flower comes a berry with up to 100 tiny seeds. The berries are green to start and deep purple or almost black when ripe. Ripe berries are sweet and were eagerly sought for food by both Māori and early European settlers. Birds, particularly the kererū, also love the berries, and this is a great method of seed dispersal. For early Māori, when the flowers appeared in September, it was a sign that it was time to plant spring crops like kūmara.

Ngāti Māhanga and Ngāti Wairere are the current kaitiaki or guardians of the Mangakōtukutuku College site.

Work on Manaakitanga Marae began in 1978. This marae currently sits at the entrance of Melville High School on Collins Road. A marae is a symbol for people, signifying leadership, prestige, honour, respect, support and knowledge.

Te Manaakitanga: To foster and nourish

Te Mataapuna: The well of knowledge

O Nga Marae Kura: The courtyard of learning

This area is already established to welcome guests, all staff, new rangatahi and whānau, and the outdoor area can also be utilised for teaching and learning.

We believe that history has a key part in influencing the design and landscape of our school. We want to look to the past to shape the future. Our iwi envisage a variety of green areas on our school site showcasing native grasses, flowers, trees, water and cool shaded areas that will benefit all rangatahi, whanau, staff and visitors. The flora will reflect the soils and it may be possible to recreate aspects of the swamps that were present around the site according to geological history.

We see furniture for learning and leisure as being a key part of the environment. We expect that these will weather the elements and could be designed to reflect the traditions of Ngāti Māhanga, Ngāti Wairere and the natural environment. The native flora, for instance, kōtukutuku (native fuchsia) raupo, harakeke (flax), ti kouka (cabbage tree), and manuka grasses can be planted to form a natural landscape and furniture placed in these areas for our students and staff to enjoy. This would also allow the native birds to inhabit the area such as tui, kereru, tree weta, ruru, dragonfly, bats, lizards, and other bird life mentioned previously. A space for a traditional water feature that signifies the ten species of native fish that are known in the Mangakōtukutuku stream would be a vital feature on our school site.

The new school site also has ample space to recreate areas and spaces that replicate the traditional gardening practices of Ngāti Māhanga and Ngāti Wairere. As part of our students’ learning, soil samples (historically peat) and swamp areas could be analysed, identified, and experimented with to think about sustainable futures in this area.

Traditionally, and even today, Māori practice planting by the moon and the stars (maramataka). Some Kura Kaupapa (total Maori Immersion Schools) implement their curriculum using this method so this will be another useful way to embed Matauranga Māori into our teaching and learning programmes. Stories around Matariki, the constellations and the natural environment could be narrated by experts, iwi elders or community residents, both Māori and non-Māori.

Showcasing cultural artworks, both historical and contemporary, that represent both iwi and our local community will add to the unique culture of our school. It will also set the tone for both inside and outside the College as a palace where beauty, aesthetics and art are valued. Whakatauki can be reflected in the design on the panelling, woodwork, and windows. Décor can be reflected around lighting, entrance desks and panelling. Colours should be selected around the native flora and fauna, for example, blue, yellow, green, purple and red.

We imagine a modern school where all curriculum areas can be given full value and will grow within creative-designed and high-quality learning and teaching spaces. We particularly want to promote Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Maths, along with 21st Century skills of inquiry, communication, collaboration, creativity, and critical thinking. Clear, safe, and covered walkways can reflect the flora and fauna of the area and cater for the wide diversity of the rangatahi who will attend the school. Because our school is a restructure of two existing schools, we understand that some of these environmental practices and landscapes may already exist around the school infrastructure; however, we believe that a refreshed and improved version is what our children in this community deserve when they attend Mangakōtukutuku College. The Board together with the MOE should ensure that some of the history is preserved and that the whole school inside and out reflects the vision, values and key competencies as set in the New Zealand Curriculum for secondary schools.

We acknowledge the key tribal leaders of Ngāti Māhanga and Ngāti Wairere who assisted our Senior Leadership Team in the creation of this proposed cultural narrative for the Establishment Board to consider. We give thanks to Matua Rik Samuels of Ngāti Māhanga who so willingly shared his time and knowledge. Matua Rik generously gave his time to our senior leadership team for professional learning, and we are grateful for his knowledge and expertise. We were also honoured to meet and learn from Dr. Ngapare Hopa of Ngāti Wairere who, as the first Māori woman Oxford scholar, we humbly sat at the feet of a giant. Dr. Pare shared with us her life experiences as a tribal member of Ngāti Wairere, a teacher and an academic. In a moment of inspiration, Dr. Pare offered us a whakatauki for our new school as a place where anything is possible, and we believe that this sets our foundation as: Te Kura Whaikaha.

We acknowledge our mana whenua representatives, Ratauhinga Turner and Anthony Rawiri on the ESB and ESB Member, Jackie Woodland for brokering relationships, partnerships and opportunities that have enabled access to key mana whenua experts. The research for this document was undertaken by Matua Heemi Walker and drafted by the Mangakōtukutuku College Senior Leadership Team.

He aha te mea nui? He tangata, he tangata, he tangata - What is the most important thing in this world?

It is people, it is people, it is people.